The Dark Legacy of Shabuta, MS

How Shabuta’s brutal past and one man’s determination are shaping our stories 100 years later.

*An image further down the article may be difficult for readers to see. Please take care of yourself, as these stories are often heavy on our hearts.

Located in Eastern Mississippi, Shabuta is home to about 400 people. With its Native American roots and foundation of enslaved labor, like much of the American south, this quiet town has a tragic history that’s changed my life.

Before its incorporation in 1865, much of the land by the Chickasawhay River was owned by the Choctaw tribe. However, the Indian Removal Act in 1830, signed by President Andrew Jackson, altered the land forever, forcing many of its residents to relocate to what is now known as Oklahoma.

While Native Americans were removed from their homes, the enslaved worked in cotton fields. Their enslavement allowed slave owners to ship their unethical cotton from Shabuta to Mobile, AL ports that would make their way into products worldwide. Free land. Free labor. Business was good for white Mississippians in the mid-19th century.

But then the confederacy lost its battle to keep human beings as property. Black folks rightfully gained their freedoms, sort of, at least on paper. This shift from free labor to the wild concept of paying people for their work created a deep animosity in those who could no longer exploit Black labor. That animosity and deep seeded hatred led to a string of lynchings in Shabuta that can still be felt today.

When you search “Shabuta” and sort by images, you will quickly find an old bridge. Bridges in America often have rich historical significance. You’ve got the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco and the Brooklyn Bridge in New York. You’ve got the Seven Mile Bridge in the Florida Keys and the Benson Bridge at the beautiful Multnomah Falls in Oregon.

Shabuta has its own, located over the historic Chickasawhay River. Some call it the Shabuta Bridge, though that’s not the name most know it by. Most know it by its nickname, The Hanging Bridge. Site of one of the more brutal stories you’ll ever read.

In 1918, two brothers, Major and Andrew Clark, and two sisters, Alma and Maggie Howze were working for a 35-year-old wealthy but failed dentist in town, Dr. E.L. Johnston. While the Clark brothers worked on Dr. Johnston’s plantation, some reports state that during his travels, Dr. Johnston developed a sexual non-consensual relationship with both Alma and Maggie, ultimately moving them into his home in Shabuta. At some point, Dr. Johnston impregnated them both, Maggie, who was 20, and her little sister, Alma, who was only 16.

While on the farm, a four-month-pregnant Maggie developed a relationship with Major. One report states that the two were planning to marry. However, her rapist Dr. Johnston objected to their plans, “violently quarreling” with Major upon hearing the news and demanding that Major leave his woman alone. Word of this quarrel made its way through town.

A short time later, Dr. Johnston died, murdered on his own property. The town of white supremacists who knew of the Johnston plantation dynamic immediately arrested Major, Andrew, Maggie, and Alma for the dentist’s murder and threw them in jail.

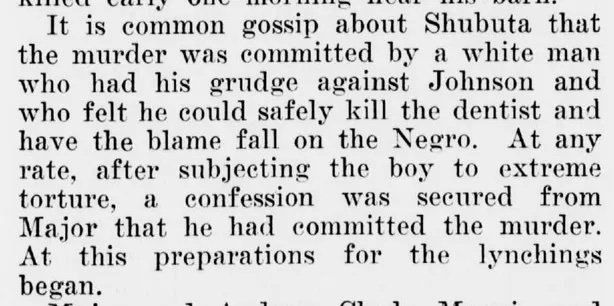

A snippet from Cayton’s Weekly, a publication that ran in Seattle, WA, in 1918.

Only Major didn’t murder Dr. Johnston. None of the four did. Instead, a white man in town who had beef with the dentist murdered him, knowing he could likely get away with it due to the widely known dynamics on his plantation between the Johnston, Major, and Maggie. The townspeople didn’t care. They wanted a Black person to pay, so they tortured a false confession out of Major and let the lynchings begin.

While in police custody, the four awaited their trial, though Shabuta’s residents had other plans. A white mob stormed the jail, and after having the Deputy Sheriff hand over the keys to their cell, the mob stole all four accused, tied them up, threw them in their vehicles, and drove them to the bridge over the Chickasawhay river.

While the mob demanded their death, Maggie, Alma, Major, and Andrew proclaimed their innocence. “I ain’t guilty of killing the doctor, and you oughtn’t to kill me,” Maggie cried. Unfortunately, Maggie’s request was met with a monkey wrench to the mouth, knocking her teeth out in the process.

The mob prepared four ropes, tying each around their necks, and one by one, they were thrown from the bridge, snapping their necks and killing them instantly.

20-year-old Maggie didn’t go quietly.

Described as a strong and vigorous woman, with a bloodied face from the monkey wrench attack, Maggie fought back, catching herself twice as she was thrown from the bridge. Though a third attempt wasn’t successful as the mob was able to throw her from the bridge, as well, killing her alongside her fiancee, her fiancee’s 16-year-old brother, and her 16-year-old sister, who was days away from giving birth.

The following day, members of the mob shared stories around the town of their lynchings, laughing at how hard it had been to kill “that big Black Jersey woman.”

For two days, the four victims hung from that bridge, still, as a reminder to the other Black folks in the area about what the mob was capable of. And while the lives of the four victims were taken immediately, eyewitnesses reported seeing movement from the eight-month-pregnant Alma’s womb while her lifeless body still hung from that bridge.

An image of 14 year old’s Ernest Green and Charlie Lang on the Hanging Bridge in 1942.

A newly formed NAACP contacted Mississippi Governor Theodore Bilbo (who once stated that Black people exercising their right to vote was “one of the most damnable demonstrations of demagoguery in our Southland”) and demanded an investigation into the lynchings. He responded by telling the group to “go to hell.”

This wasn’t the only case of lynchings from that bridge. Children Ernest Green and Charlie Lang were hung from the bridge in 1942 for allegedly attempting to rape an unknown white girl.

Following the 1942 lynchings, an investigator visited the area, speaking to locals about their town. When asked about what the bridge was used for, a local man stated, “We just keep it for stringing up niggers.”

As of March 2023, while no longer operable, the Hanging Bridge still stands.

Shabuta was not safe for Black people. Much of the Jim Crow south wasn’t. Beginning in 1910, Black folks left the south in droves, working to find safer communities in places like Chicago, Detroit, Baltimore, etc.

While some were recruited out of the south for specific employment opportunities, others worked as connectors, packing up families and communities and moving them North to safer communities. Shabuta had a man like this, Reverend Louis W. Parson, nicknamed Modern Day Moses.

Beginning in 1927, Reverend Parson and his wife, Frances, moved from Shabuta, ultimately landing in Albany, NY, where he would purchase 14 acres of land to begin building a community. For years, Parson would travel back to the south, recruiting Black families to move their families up to Albany, where they could live safer, more secure lives, free from the threat of lynchings and white supremacy.

Parson built this community on Rapp Road in Albany, working with families to build something special in the area. Securing land that could be used for hunting and farming, just like they did in the south. In addition to building community, the Parsons also helped build the First Church of God in Christ in Albany, now called the Wilborn Temple, at 79 Hamilton St.

While Parson died in 1940, residents of the Church and Rapp Road continued to build lives away from the southern persecution, creating a legacy that would be recognized in 2002 when the Rapp Road Community was designated as a New York State Historic District, ultimately being recognized as a National Historic District.

Part of Parson’s legacy included moving several of his own family members to Rapp Road, including his young niece, Orlean. Born in 1922, Orlean would grow up to have nine children, raising them in the Albany area.

Orlean’s story means a lot to me because it’s personal. Orlean was my paternal Grandmother, and while my time with her was brief and too long ago for me to remember, Shabuta’s own Reverend Louis Parson’s decision to move his neighbors out of the south following a set of brutal lynchings set the scene for the life I’m living today.

Our lives are deeply connected, allowing the intentionality we lead with today to outlive our earthly presence, impacting those we’ll never know.

All my life, I considered myself a New Yorker who made his way to California, where I settled down and created my life. But in 2020, when I sat down with my biological father to ask questions and dig deeper into how his decisions as a father have affected mine, I learned about our southern roots. I learned about the historical hardships. My assumptions became a reality as I learned how my Queensbury, NY, upbringing actually began in Shabuta, MS, long before I was ever a thought.

The connection between the past and our present has never been more apparent. With a history like the atrocities on the Hanging Bridge still looming today, it’s no wonder Mississippi is still strategically working to silence Black voices, less violently but just as purposeful as the mob who killed the Howze sisters and Clark brothers in 1918.

Time and distance may affect how we view these events, allowing the days between them to dictate their weight on our lives. But time and again, we are reminded how our history lives well within our story, and no matter how hard and brutal, our stories are worth telling for generations to come.